The term “co-dependency” was

initially coined by Alcoholics Anonymous in 1950 to describe those individuals

whose unhealthy choices enable and encourage their partner with addiction.

While this is still true, co-dependency more recently has a much broader

definition. Although it is not recognized as a clinical diagnosis or a

personality disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM), co-dependency is an unhealthy and potentially toxic relational

dynamic. Commonly known as “relationship addiction”, co-dependency involves

emotional, spiritual, physical, or mental enmeshment with a loved one.

Enmeshment simply means growing up in a family system that lacks boundaries (e.g.,

how you feel about me is how I feel about myself, what is yours is mine and

what is mine is yours, and if one family member is in trouble, the whole family

is, sound familiar?).

Dr. Renee Exelbert, a clinical

psychologist, classifies an adult relationship as co-dependent when one partner

known as “the taker” needs the other partner “the giver”, who in turn, needs to

be needed. Co-dependent relationships are thus constructed around an inequity

of power that promotes the needs of the “taker,” while leaving the “giver” to

sacrifice themselves, walk on eggshells to avoid conflict, and feel the need to

constantly apologize, even when they have not done anything wrong.

Individuals who are co-dependent

are usually well-intentioned without realizing they are sabotaging the

relationship by caring excessively for the person who is struggling. By

constantly rescuing, saving, and providing financial support, the “giver’ is

enabling the “taker” to become more dependent on them. The “giver” who likes to

“be needed” often gets satisfaction by being recognized for their service;

however, this can only go on for so long before the choices the “giver” makes

backfires.

For some “givers”, co-dependent

relationships become commonplace, and they subconsciously gravitate to these

relationships because their brain likes what is familiar to them. Over time,

they end up seeking romantic relationships and friendships where they are

encouraged to behave as “martyrs” – devoting all their time and energy to care

for others who are often emotionally unavailable, and thus completely lose

sight of what is important to them.

Why Co-Dependency

Happens?

Co-dependency is learned in a

dysfunctional family dynamic by watching other family members display co-dependency.

It is often passed down from one generation to the next. In a functional family

dynamic, a child is nurtured while their dependency and developmental needs are

properly met, allowing them to grow up to be healthy adults with a sense of

autonomy. In a dysfunctional family, when a child’s dependency and

developmental needs are not met, they become an adult with a child’s needs,

described as “adult children” by Dr. John Bradshaw.

Co-dependency is a trauma

response to the stress a child is exposed to growing up in a dysfunctional

family. According to Dr. Gabor Mate, excess stress occurs when the demands made

on a child exceed his developmental capacity to fulfill. The most common

drivers of stress on children are a lack of control, a lack of information, and

a lack of certainty. Frequent stressors to children growing up in dysfunctional

families include abandonment, parental rage, addiction, and physical abuse—all of which

are out of the child’s control and capacity to comprehend. When there is so

much tension and stress in a family, no family member can attend to their own

needs. Each member ends up “de-selfing” to try and exert some control over the

family situation.

For those children who are

habitually exposed to stress and the chaotic conditions of a dysfunctional

family system, it is the lack of stress in their adult lives that evokes

boredom and a sense of uneasiness. In other words, these same children become

addicted to the cortisol released from chronic exposure to stress. And as

“adult children,” they unconsciously desire stress, whereby it is the absence

of stress that makes them feel as though things are not normal.

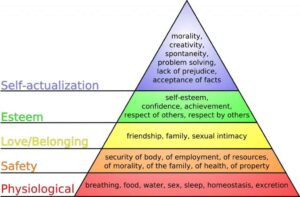

Perhaps the best way to explain

the concept of growing up in a dysfunctional family is through Maslow’s hierarchy

of needs, a psychological theory of motivation proposed by Abraham Maslow in

1943. His theory states that humans have basic, psychological, and

self-fulfillment needs, which he divides into five categories that determine

individual behavior: (1) physiological, (2) safety, (3) belongingness &

love, (4) esteem, and (5) self-actualization. As a humanist, Maslow believed

that individuals are born with a desire to become self-actualized or to be all

they can be in life. But for that to happen, humans need their basic needs met

first. If we look at these hierarchal needs in the context of growing up in a

dysfunctional family system, we realize that these “adult children” carry a

wounded inner child who was deprived of their fundamental developmental needs

as children and perhaps can only go so far in achieving their potential in

life.

Just like a war veteran who

develops post-traumatic stress disorder, the child learns to adapt, and their

autonomic nervous system prepares them for flight or flight or flee response.

They become hypervigilant to the threat, their heart rate goes up, muscles

become tenser, and blood vessels constrict to shift the blood to the body parts

that oversee the “fight or flight or flee” reaction. These physiological

changes in their bodies are intended as a “survival state” until the situation

is normalized in their mind.

To survive the harsh conditions

of growing up in a dysfunctional family system, a child learns to deny abuse by

idealizing their parents and shifting the blame onto themselves, believing that,

“I must have done something bad to receive this harsh treatment from my

parents.” A child will also dissociate from their body to tolerate the abuse.

They learn how to repress, identify, or re-enact the pain. As a child growing

up with these survival strategies, it becomes part of who they are as “adult

children,” and they enter their adult relationships with this unfinished

business from their childhood. Each ‘battle’ is not a new engagement, but a

continuation of an old war with no victor. Thus, co-dependency is a survival

behavior a child learns to master in order to overcome toxic dysfunctional

family dynamics.

The Spanish existentialist and

philosopher José Ortega y Gasset used the word “otheration” to describe those

who are co-dependent, when their lives are dominated by what others think of

them. As “adult children”, co-dependent adults end up with a fragile self-image

and learn to guard against (hypervigilance) the outside perceptions of that

self-image. Because of their dysfunctional upbringing, they believe they are

responsible for what others think about them (e.g., how you feel about me is how

I feel about myself). They deceive themselves by detaching from their authentic

being to be what others want and expect of them.

Growing up in a dysfunctional

family system, I was called the hero of the family, the overachiever who always

excelled in the hope of getting some attention from my caregivers. I did not even

allow the word “impossible” to enter my vocabulary. I would do whatever it took

to get to where I needed to be to impress my parents – whether it be straight

As, academic accolades, or scholarships etc. Consequently, now as an “adult

child”, I continue to overachieve in order to reach the self-actualization

goals that Maslow described. However, my addiction to overachieving is simply

to cover up the void left by my wounded inner child. A shroud of accomplishment

that I drape over my internal void.

Another thing that promotes

co-dependency is our cultural practices and understanding of religious beliefs.

Growing up in a patriarchal society with conservative values, I remember my

mother telling me that males and females were born incomplete, and it was only

through marriage that they completed each other. So, to my mother, a woman is

seen as a man’s better half, and a man is a woman’s other half. From the day I

developed an understanding of society, I was told that my destiny was to be the

better half of ‘Mr. Right’, and I would be obligated to give my life to him. I

was not encouraged to be an independent professional with strong interpersonal

skills, regardless of how much I surpassed my brothers in professional and

personal accomplishments. I was always told that I needed a ‘Mr. Right’, the proverbial

‘Prince Charming’ that would come to my rescue and save me.

Additionally, I grew up

listening to music with lyrics that enabled a co-dependent understanding of

love and romance. I also received religious teaching that promoted a

co-dependent family dynamic, where regardless of the wrongs your parents have

inflicted on you, they are always right, and like an obedient child it was my

religious duty to apologize and beg forgiveness from them. I grew up watching

my cousins and siblings get married with the same cultural and religious

notions of marriage, more entwined with desperation than desire. We were seldom

taught self-love or self-discipline. Thus, how can we be expected to value

others if we fail to appreciate the very essence of our own authenticity? How

can we genuinely love someone else, when we are forsaken to carry the weight of

a wounded child deprived of affection within us? And how can we spiritually

belong to someone when we are emotionally bankrupt from the “otheration” that

society, culture, and parenting expected of us? This explains many of those

generations of adult children who become enmeshed in their family systems and

in so doing, find themselves robbed of their authentic needs.

Intensifying this dynamic, our

educational system is no help when it comes to co-dependency. As academics and educators,

we are wired to value hard skills, clearly identifiable capabilities that are

black and white, easily gradable, and quantifiable; skills that give us instant

gratification and a quick surge of dopamine. If you believe in one thing, you

are seen as that singular thing only, with no gray area allowed. As a result, we

rarely invest time and energy to educate the right hemisphere of our brains,

which houses our innovation, creativity, emotions, and holistic thinking. And

afterwards, these skills are hard to measure and come with a lot of

uncertainty.

For example, how many of us are

caught up with our online personas? How far are we digitally going with these

filters that present an idealized image designed to get us the greatest number

of “likes?” And how many times do we incessantly check the number of “likes” we

receive? The more “likes” we get, the better we feel about the filtered persona

we package and post online. This is rooted in our need for validation from

growing up in a dysfunctional system that deprived us of our basic

developmental needs. To fill the void, we rush to social media, text, and email

in the hope of getting a quick surge of dopamine through the buzz, flash, or

beeps we get. Each positive notification is a digitized hug for the child we

once were, recreating the support we were deprived of when we needed it most.

Consequences of

Co-Dependency

all our adult relationships as co-dependents carrying that wounded child within

us. This list is not all-inclusive, but if you see yourself in any of these

scenarios you may want to seek help:

partner when they are not around or do not instantly return a call or text. You

almost never feel satisfied in your adult relationships.

2. You have addictive or compulsive

behaviors (not limited to substances.)

3. You are drawn to emotionally

unavailable and needy people.

4. You try to fill the void in

your life with food, chemicals, spending money, activities, etc.

5. You are an overachiever and have

unrealistic expectations of yourself.

6. You are afraid of boundaries

and often confused about what you really stand for.

7. You do not trust anyone,

including yourself.

8. You re-enact your childhood

traumas in your adult relationships.

9. You feel your worth relies on

what others think of you.

10. You are “spiritually

bankrupt”, and your happiness lies outside of you.

11. You carry the weight of the

world on your shoulders and feel responsible for everyone else’s pain.

12. Your try to control every situation

by being helpful, often becoming frustrated when things get out of control.

13. You constantly seek approval

and validation from others.

The Mastery of Self

So, here we are, having missed

all our basic development needs as children and consequently doomed for the

rest of our adult lives. Fortunately, this is not the case. And I say this

because of neuroplasticity, which is the brain’s ability to change and adjust

if you are willing to put in the work. We can unlearn all the patterns that we

learned growing up once we know how.

As I started writing this blog;

I had to re-learn the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous because each step

carries so much wisdom. When a person with alcohol addiction seeks recovery,

the first thing they need to do is have the courage to admit they have a

problem, and in a way, they are overcoming their armor of shame. The strategies

that I propose to master co-dependency are very much in line with the 12 steps

of Alcoholics Anonymous.

The road to self-mastery always

starts with admitting you have a problem. And to do so, you must cast off all

the shame-based armor that you have worn over the years. The only way to

overcome co-dependency and shame is by being willing to go through the pain and

face the wounds of your inner child. This is only possible if we allow

ourselves to grieve the loss of our unmet development needs. We must come to

terms with the fact that our childhood is gone, and it will not come back.

My circle of trusted friends

called me a professional co-dependent because I have managed to hide the wounds

suffered by my inner child with professional achievements. As someone in

recovery from co-dependency, I had to identify a new family, a family that is

free of shame and judgment, a family that has endured the same pain and

suffering as myself, so I could mirror and seek guidance from them when needed.

This new family, known as a

support group, has different rules, dynamics, and systems from the one in which

we were raised. They accept our authentic self; welcome us with our flaws and often

tell us that they too have been there and know how we feel.

Through honest sharing and

mirroring, we slowly recover our self-esteem and overcome the shame that we

have been carrying all these years. In this new family system that we identify,

we can start expressing the anger and sadness that we have repressed over the

years. Anger, frustration, and sadness are all energies that were meant to flow

out of our body at the right time, in the same way an engine emits exhaust.

As you continue your journey of

recovery, it is time to end the delusions about your family of origin. You need

to believe that you can leave home and must learn to detach yourself from their

beliefs and ideologies which do not match up with your own conscience. I felt a

lot of guilt during this process, but as they say, no pain, no gain. And the

only way to get it done is to have the courage to break the ensnarement of your

familial baggage and to refocus your energy on your own wellbeing. Just because

you came from someone, does not mean that you belong to them.

As spiritual beings living on

earth, we are all here to serve a purpose; however, our souls have been deprived

of meaning over the years. We have managed to show that perfect persona to the

outside world and uphold a crumbling façade in the hopes we would eventually

believe it ourselves. We have managed to show how blessed we are to have an

ideal marriage, family, job, and living conditions, yet we wake up every

morning disconnected from our souls and the very essence of what makes us a being.

It is time to put fuel back into your spiritual tank. It is time to connect to

your body and soul through meditation, prayers, or whatever connects you to a

higher source. There is a silent energy emanating all around us and once you

dial into this frequency you will realize it is the symphony of encouragement

that was always missing.

The Wisdom of Suffering

I end with a quote by my

favorite logo-therapist, Dr. Victor Frankl in his book, A Man’s Search

for Meaning, “if there is any meaning in life at all, there must be a

meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate

and death. Without suffering and death, human life cannot be complete.” Wisdom

often comes from bad experiences, and because there is wisdom in every

suffering, it is the survivors of suffering that make the most interesting people

at any dinner table. Our scars have stories to tell, and our smiles usually

hold a harrowing story of survival for those willing to let us share it. Such

survivors are the ones I want with me when I explore the world. Let your

suffering be your calling, a clarion call to discover all possibilities without

fear.